Sophie van den Elzen

“Was it not Harriet Beecher Stowe?” Some Thoughts on Cultural Appropriation from the Perspective of Nineteenth-Century Activism

Over the last fifteen years, there has been an upsurge in public interest for ‘cultural appropriation’, popularly understood as the adoption of distinctive elements of a culture by people who do not belong to that culture (see, for instance, James O. Young’s book on cultural appropriation and the arts). Rather than referring to a natural feature of cultural production, the term has gained negative connotations, becoming a shorthand for offensive stereotypes and artists’ transgression of common decorum when voicing experiences that are not theirs. The latest global ripple of discussion was started by the novelist Lionel Shriver’s keynote speech at the Brisbane Writers Festival in September of 2016 , which was published in full by The Guardian.

Lionel Shriver at the Brisbane Writers Festival

Shriver, donning a sombrero, launched into a meaty reductio ad absurdum using examples from US college life, her childhood and literary classics to demonstrate how the notion of cultural appropriation as a negative is a flaccid product of a “world of identity politics,” composite of safe spaces. Because it restricts writers’ creativity by dictating they cannot inhibit other experiences than their own and validates the restriction of freedom of expression, she hoped that the notion would be a “passing fad”. Her speech spawned passionate responses worldwide, often from colleagues in the same profession, a significant part of whom found her speech profoundly offensive.

Many arguments against cultural appropriation center on the jarring fact that well-meant ventriloquism sells, or rather, will be picked up to be sold by a publisher, where authentic experiences from a member of a minority often will not. Another major thread in these arguments is that this form of cultural transfer runs in only one direction. Where an exemplar of the majority (white, middle-class, male) can don personas that don’t come from his own experience, minority writers who do the same are heavily criticized, as their art is marketed as inextricably bound up with their situated experiences. Commentators who find themselves in Shriver’s camp, however, don’t regard cultural appropriation as a useful term in cultural critique, claiming that it is not only a natural feature of culture but also a tool for fostering cross-cultural understanding.

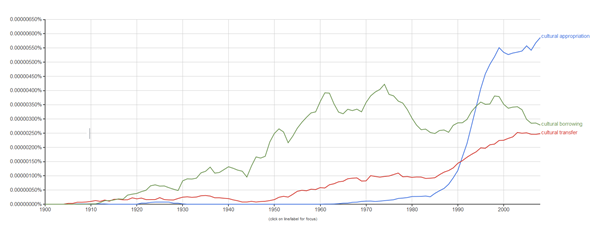

Pejorative connotations of the word “appropriation” of theft and (illegitimate) ownership certainly feed into the vitriol with which it is debated. However, the one-way-traffic conjured by its definition as “taking exclusive possession” of a thing (Merriam-Webster) makes that it is not just a catch word of a “seasonal controversy” but a mighty tool for analyzing cultural expressions, a concept which serves the analyst as a constant reminder of the power hierarchies and stringent divisions of the real world. Its directionality makes it much more precise in this regard than some of its counterpart concepts, ‘cultural transfer’ and ‘cultural borrowing’, used to describe the same ancient and ubiquitous attendant process of socialization. This might offer one explanation why, though late to the scene, the concept of cultural appropriation took off so much more effectively and why, in the nineties, it could be called both the “new magic word in cultural history” and the “magic word in new cultural history”.

cultural appropriation vs. cultural transfer vs. cultural borrowing: a quick Google N-Gram (click for more)

Though arguably not dealing with cultural appropriation in the popular sense, my PhD research tinged the way I engaged with these recent debates, bringing out two points which I would like to offer in the remainder of this blog post.

My PhD project studies the transference of images and narratives from the Anglo-American antislavery movements to nineteenth-century European women’s movements. This transference ranges from discussions of American slavery to illustrate European women’s social inequality, through reference to the successes of those whom they considered their (white) American antislavery ‘foremothers’, to(proto-)feminist texts using the language, conceptualizations and rhetorical tools developed by antislavery campaigns.

It is not a study of solidarity across movements, but rather an effort to chart the rhetorical effects of conjuring one potent collective memory in service of another cause.

As these references and borrowings often took place within a transnational social network of (female) reformers of similar class backgrounds, the power imbalances are murkier, the cultural borders crossed more nebulous, and the application of the label of cultural appropriation more up for debate. Studying these texts holds relevance for our understanding of the issue, however, as it disambiguates it in two ways: 1) it does not allow for the discussion to derail into the quagmire of authorial intention and 2) it showcases the dangerous ease with which the radical potential of affective power can be appropriated.

I have recently been spending time with 22 volumes (1893-1914) of a bi-weekly women’s periodical headed by outspoken Dutch women’s activist Wilhelmina Drucker, Evolutie (Evolution). Drucker was a cosmopolitan-minded woman in whose mind women’s emancipation neatly aligned with other global struggles against oppression. Evolutie often references American slavery and routinely evokes the trope of slavery to viscerally express the injustices against women its writers perceived. In 1893, for instance, it reproduces sections of Edouard Laboulaye’s fairy-tale Prince Caniche in which the protagonist visits Monrovia, the city where former slaves have built a society on American principles of liberty. It also frequently heralds famous abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison for his refusal to partake in the 1840 London Anti-Slavery Convention when they wouldn’t allow women to join, and Harriet Beecher Stowe as an example of what women can achieve for the good of humankind.

Where discussions of cultural appropriation often spend much time speculating on the elusive issue of authorial intention (e.g. fostering awareness or ridiculing), the purpose of Evolutie is overt: it presents international news, serialized fiction and controversial opinions to entertain, but ultimately promote the women’s cause. Some form of ideological grounding and ultimate purpose, however, is much closer to the reality of much of cultural consumption than the conception of artistic production that is generally used in discussions of cultural appropriation. In her piece, too, Shriver conceives of the writer as a solitary creative spirit offering readers the “enormous relief to escape the confines of [their] own head.” This is a quite narrow conception of the profession, as an ideal culturally and historically specific, and, one might even think, outmoded. Presenting writing as a profession that historically did not deal with, and still should not have to deal with politics, ethical debates or public backlash to ensure its artistic quality hence risks being deceptive.

When Evolutie discusses American slavery, it does so with the purpose of promoting European women’s causes, and in the process distorts the cultural memory of slavery. William Lloyd Garrison, for instance, is recast as primarily a women’s activist. Sometimes, despite the knowledge of the brutality of the American institution that abolitionist campaigns had spread in Europe, slavery is uncomplicatedly presented as an analogical practice to how women are treated (“How illogically did those men, gathered to end the slavery of negroes, act when they started by upholding the slavery that presses down upon half the human race”). At other times, the institution of slavery is represented as a definitively vanquished relic of barbarism against which women’s oppression can be contrasted for shock value (“Even in the most civilized Germanic marriages one finds… the most disgraceful slavery, brutalism that is no longer of our age”).The end of slavery is recast as an effort of (white) women’s activists, and primarily of Harriet Beecher Stowe (“Who forced the people of the world to direct their gaze to a so-called civilized nation that, for no other reason than that they were black, saw their brothers as cattle to be traded? Was it not Harriet Beecher Stowe, a women who activated the entire world?”).

Distorting a cultural memory is a colossal effect that is achieved with considerable ease. Contrary to approaches literary works often tempt readers to, there is no need here to guess why the texts in Evolutie do so; its new forms serve the rhetorical purpose of promoting women’s causes. These texts harvest the affective power of one cultural memory for another by emptying it and making it into a harbinger, a symbol, one link in a chain.

This particular case of appropriation, however, is only a blatant example of the instrumentalization and symbolization ubiquitous in and often part of the structural integrity of artistic practices. It also underlies choices like Shriver’s to feature an African American side character with early onset dementia “because arm candy of color would reflect well on [the protagonist] in his circle…but in the end the joke is on him.” Critical attention for how these processes take place exactly, what purposes are served and what is erased in the process is not only an aesthetic, but an ethical dimension of literary analysis, cultural criticism and public interpretation at large. Moreover, to me, it does not follow from its ubiquity that the practice should be beyond reflection or reproach, as Shriver argues. To consider it so limits our potential to come to new insights through opening public debate to different voices in a time where possibilities for democratic global discussion seem more achievable and as tantalizingly interesting as ever.