Blog

Between the Paradigms: Youth Representatives and Local Governance in Timor-Leste

Simão[1] is twenty-seven years old, lives in Dili (the capital city) and his family comes from Viqueque, one of the three eastern-most districts of Timor-Leste (East Timor[2]). After finishing high school he participated in a few vocational trainings and so he learned a thing or two about computers and about construction. Then, in 2009, the candidate running for the position of xefe suku (village[3] leader) asked him to become part of his team as a youth representative. Simão agreed for various reasons. Firstly, the xefe suku was running as a candidate for the political party FRETILIN[4] and Simão’s family is also a FRETILIN family. As he told me “I am with the FRETILIN because that comes with the family. Both my father and my mother belong to it so I have to belong to it too, I cannot go to another one. (…) Because my parents taught me that the FRETILIN was the only party that really wanted independence for Timor, so I follow those words”. Secondly, he wanted “to create unity and friendship, help our suku in order to improve our nation, from the suku to the nation”. And thirdly, Simão was already active in his suku anyway, so why not make it official. Simão tells me all of this sitting on a green wooden bench in the gardens of the faculty of education of the National University of Timor-Leste. Although at first confused that a white European academic wants to interview him – a mere youth representative – he gradually gains confidence and paints an increasingly detailed picture of his experiences as a youth representative in an urban suku in Timor-Leste.

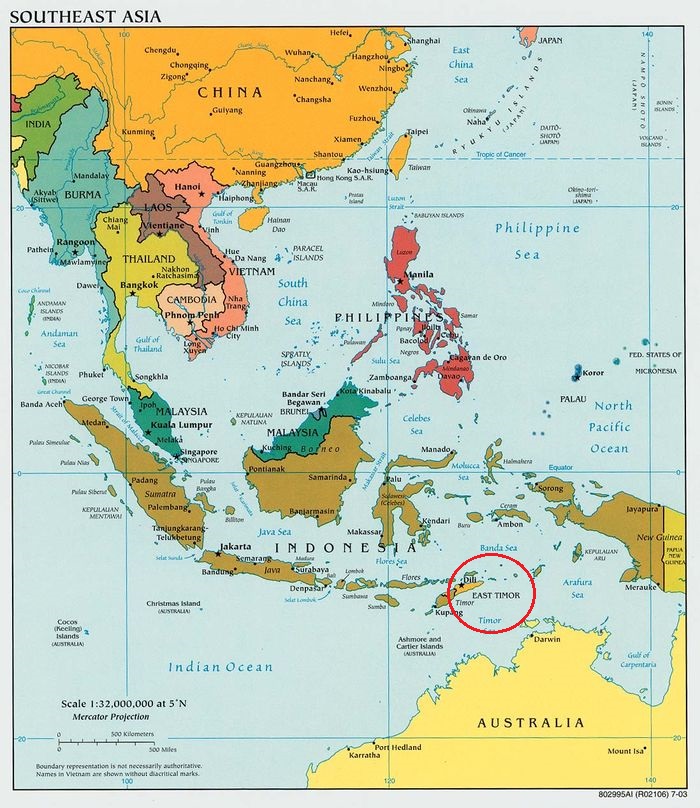

Timor-Leste has been an independent nation-state since 2002 and occupies the eastern half of the Timor Island which was divided into two parts by Portuguese and Dutch colonial administrations in the nineteenth century. The western half became Indonesian territory upon Indonesian independence from the Netherlands while the eastern half remained under Portuguese colonial administration until the end of the Salazar-Caetano dictatorship in Portugal in 1974.

After a brief but bloody conflict between three Timorese parties that envisioned different solutions for the East Timorese independence, the FRETILIN (Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor) declared unilateral independence in 1975. A few days later, Indonesian forces invaded East Timorese territory ensuing an occupation that was brutal and alienating. The occupation would only end, after twenty-four years of resistance, with a referendum coordinated by the United Nations in 1999 in which 78.5% of the population voted for independence from Indonesia. During its occupation of East Timor, Indonesia invested heavily in building up infrastructure and an educational system. Therefore it relied heavily however, on immigrated Indonesian officials to run state affairs. The vote for independence triggered the departure and flight of these Indonesian bureaucrats together with rampaging, destruction, looting and burning of 70% of the country’s infrastructure by Indonesian military and pro-Indonesia militias. This led the incoming United Nations transitional administration to assume that no institutions of governance were left standing and to adopt a tabula rasa approach to East Timorese state-building.

Contrary to the assumption of the UN and other international state-builders that were involved in the early years of East Timorese independence, Timor-Leste was by no means a governmental tabula rasa. During the early years of state-building, different systems of governance – customary and new, indigenous and foreign – were interwoven, resulting in a complex hybrid system. This hybridity and the place young adults have in it, constitute the focus of my qualitative and ethnographic PhD research. My purpose here is to show what it means for youth representatives like Simão, to navigate the messy entanglement of diverse forms of governance in a post-conflict momentum of democratization and state-building.

Let us go back for that, to the suku, the governmental entity at the level of which Simão represents youth. The suku in Timor-Leste is much more than the lowest level of governance. It is both a territorial and a social unit of belonging. One suku is mostly composed by a number of families and their respective descent lines that are intimately connected through relationships of reciprocal exchange and intermarriage. Each descent line is connected to an Uma Lulik (‘sacred house’) that connects them with the other members of the extended family and with the spirits of their ancestors. It is the Uma Lulik, and one’s position in it, that defines the relationship of the individual with the other individuals in the suku. Hence, when Simão introduced himself to me, it was important to add that, although he has been living in Dili most of his life, his family comes from the Viqueque district. Because it is in the Viqueque district that his Uma Lulik stands. The (mostly rural) suku of origin of the family is mostly considered by people to be their ‘true’ suku, even if they are second-generation Dili inhabitants. Although for a considerable part of the young and urban East Timorese population the kinship relationships no longer define who they choose as a marriage partner, the Uma Lulik and its related family interconnections do play an important role in young adult’s social and economic lives.

The Uma Lulik and its family relationships not only defines kinship belonging, it also defines who are entitled to solve conflicts in the community according to customary law. These are mostly elderly men respected in the community.[5] Despite co-optation, marginalization or even destruction of higher-order political structures by both the Portuguese and Indonesian occupying forces, systems of customary law and kinship relationships were a basis for continuity under colonial oppression and these customary structures often played a much more significant role in the daily life of the community than the colonial administrations did.[6] Hence, the overlooking of these local systems of customary law by international state-builders and the erroneous assumption that Timor-Leste was a governmental tabula rasa, added the UN and other international agencies to the list of foreign state-building forces over the centuries that would be unable to grasp, let alone permeate local power structures and governance.

There were, however, over the course of state-building, various attempts to incorporate the local level of governance into the national liberal-democratic system. These efforts resulted in the creation and election of suku councils such as the one Simão was part of. Simão was not the only one asked by the candidate xefe suku to be part of the council. In 2009, when Simão’s xefe suku was elected, the suku law ordered the creation of pakotes (packages) in which the xefe suku gathered one xefe for each aldeia (sub-division of the suku) in his suku, as well as two women’s representatives, two youth representatives (one man and one woman) and one community elder. Citizens then elected one out of the presented pakotes to become their suku council.

Suku councils became an interesting and hybrid form of local governance composed by leaders who fit local customary understandings of governing legitimacy[7] (male seniority, often from ‘royal’ descent), leaders who fit post-conflict national political legitimacy (being veterans of the (armed) resistance against Indonesia) and ‘modern’ democratic representatives for women and youth (groups often disadvantaged in customary governance).

The stories that Simão and other youth representatives told me, both in urban and in rural suku, showed that to be what Cummins[8] calls a ‘new institutional figure’ among ‘old institutional figures’ is all but just a position in a local body of governance. It is a complicated position between paradigms that requires a complex set of skills and that brings about high expectations and strong disappointments, making the position of youth representative in an East Timorese suku a challenging at best, and demotivating and disempowering position at worst.

To illustrate this point, let us return, once more to Simão. As a youth representative, Simão receives a small fee to compensate him for his activities. This fee is conditional on attending the suku council meetings. The fact that youth representatives and other suku council members receive money from the state, makes them, in the eyes of many people, part of the state. The idea that youth representatives ‘eat from the state’ was mentioned a few times in my presence. This money is, however, not in any way comparable to a salary and hence many youth representatives take up jobs next to their suku council function. It happens that these jobs are so demanding that they do no longer have time for their youth representative activities. Thus, when I visited the suku council of the suku I lived in and asked to speak to the youth representatives, the secretary had to consult a list, as she had no idea who the youth representatives were. This situation leads to frustrations on both sides. Simão told me he addressed national leaders telling them that the limited compensation discourages youth representatives to engage and he reported “they say: ‘when there is a meeting you go, that is what we give you the money for, not for you to do work’”. On the other hand, the youth in the suku and partly also the other suku council members expect youth representatives to be engaged full-time for the good of the youth population. A xefe suku of a rural village I came to know well always complained that the youth representatives never took any initiative. Youth in that same village complained that the youth representatives never did anything for them. Urban youth whom I asked to introduce me to their youth representatives told me they had no idea who they were.

My friend Rafael was a local NGO’s youth volunteer coordinator for one of Dili’s sub-districts and that is why he knew many youth representatives, including Simão. Rafael was not very positive about suku youth representatives either. When I narrated to him the incident with the secretary who had to look up the names of the youth representatives of my own suku he told me:

It is a very big problem…they do not work! And the problems among youth, it has to be the xefe suku going there directly himself. Like recently the youth at the Comoro Market. It was the xefe suku going there. So I asked him where the youth representatives were. And he told me that they were afraid, because these are youth who make problems, who commit crimes, so the youth representative, what was he going to do? Now this xefe suku likes to talk with me in such a funny way. So I don’t know whether it was true. Maybe they just did not have time to come. But still, the responsibility is theirs…so at that time they were not there.

This account contrasts sharply with what Simão told me about his own possibilities to participate in the resolution of problems between youth.

Simão: we recently had a problem with youth, they had a problem, they were drunk and I called the police. The police came and calmed the situation and after the situation we sat in the suku office. I had informed the xefe suku and the Lia Nain (elder). Because it was youth from our suku with youth from another suku, I informed the xefe suku and he proposed to make a letter in order to call the others to come to our suku office. So I prepared a letter and called them, from both sides. I managed both groups to come and sit together. I do not have the power to handle it so I gave it to the xefe suku and the Lia Nain. They looked for a solution and made peace.

Sara: but so in these kind of situations, the role of the youth representative is to call everybody to come together but when it comes to solving the problem it is the xefe suku and the Lia Nain who do that?

Simão: yes

Sara: why?

Simão: because they are the ones who have power. They know how to talk with power. I can only send the letter to call people together. Because in our structure, the biggest power is with the xefe suku and then the Lia Nain. If there is a problem in the aldeia, I first check with the xefe aldeia, then de xefe aldeia checks with the youth who made problems and brings them to the suku office and then the xefe suku comes to investigate them.

Sara: yes, and are there problems that the youth representative can solve alone?

Simão: no

Sara: so you always have to call the xefe suku?

Simão: yes

What Simão and Rafael show us here is the profound disjuncture between what is expected from youth representatives from ‘above’ and from ‘below’. On a higher level they illustrate the disjuncture between the two paradigms at work in the sphere of local governance and the precarious place youth representatives occupy in this disjuncture. As ‘new institutional figures’ brought in by a paradigm of liberal-democratic horizontal representation in which all citizens have the right to be treated equally, they are confronted with customary hierarchies in which they occupy the very bottom of the legitimacy ladder. I do not mean to present liberal democracy here as ‘modern’ and contrast it to customary governance as ‘traditional’ and ‘backward’. The complex and fascinating hybrids created in East Timorese local governance show that they can be simultaneous and profoundly enmeshed processes. However, what the case of East Timorese local governance also shows is that the blind implementation of liberal-democratic forms of representation in presumed tabula rasa situations might create disjointed and frustrating positions for those who are supposedly empowered by it.

[1] All names of research participants are pseudonyms to guarantee their anonymity. Quotes are translated from Tetun to English by the author.

[2] Although officially Timor-Leste can also be referred to as East Timor, for the sake of clarity I use Timor-Leste when referring to the independent nation-state and East Timor when referring to the territory occupied by Indonesia, previous to independence. I use East Timorese to refer to nationality.

[3] Although suku translates roughly as village it is also used in the urban sphere – constituting governmental sub-divisions of the city. This was the case for the urban suku in which Simão lived.

[4] FRETILIN: Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor. One of the major political parties in Timor-Leste today.

[5] Although in some (matrilineal) communities elderly women also play a role in customary law, the public domain of politics is mostly regarded as the arena of men (see for example Cummins, Deborah. 2011. ‘The problem of gender quotas: women’s representatives on Timor-Leste’s suku councils’. Development in Practice 21(1): 85-95).

[6] McWilliam, Andrew. 2005. ‘Houses of Resistance in East Timor: Structuring Sociality in the New Nation’. Anthropological Forum 15(1): 27-44. Page 38.

[7] See for example Cummins, Deborah and Michael Leach. 2012. ‘Democracy Old and New: The Interaction of Modern and Traditional Authority in East Timorese Local Government’. Asian Politics and Policy 4(1): 89-104.

[8] Cummins 2011, 93.